Suicide: Who is at risk and how do we prevent it?

Talking about suicide openly and directly is very important. It won’t introduce the idea into someone’s thinking who isn’t already considering suicide. Engaging in meaningful dialogue about difficult topics is essential to being able to end the world’s suicide epidemic.

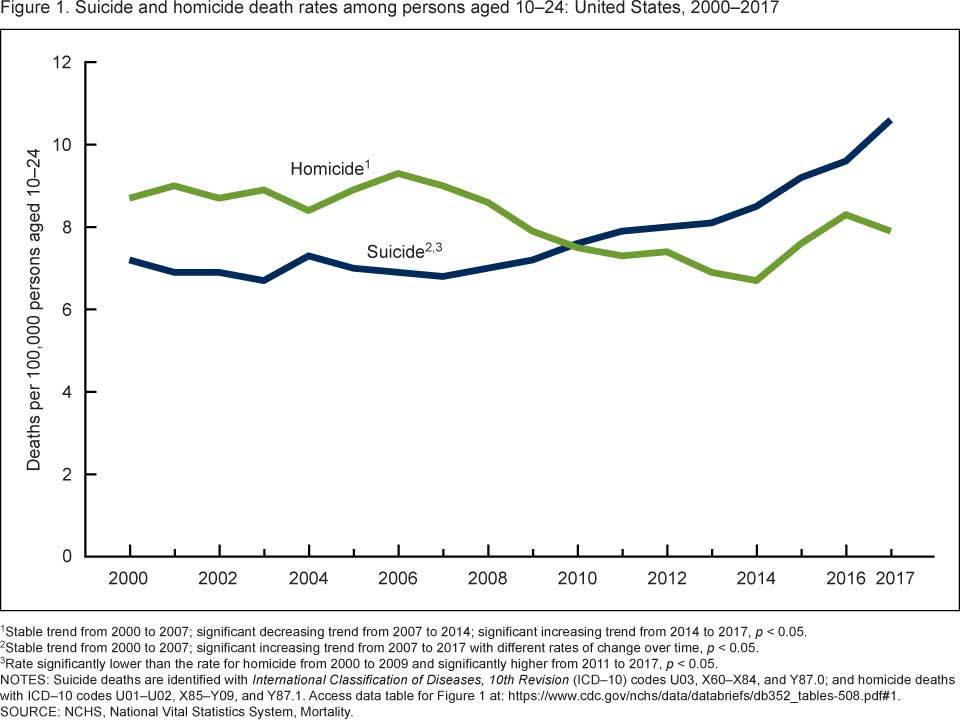

Deaths from suicide increased dramatically in the last decade. Suicide rates went up more than 30 percent in half of states between 1999 and 2018. Among young people ages 10 to 24, the suicide rate increased 56 percent between 2007 and 2017, and in 2017 suicide was the second leading cause of death for young Americans ages 15 to 24.

The suicide rate among young people ages 10 to 24 increased 56% between 2007 and 2017.

Suicide-related behaviors are complicated and are rarely the result of a single factor or event in someone’s life. Researchers are working to expand our knowledge of what combination of factors make someone most vulnerable as well as potential points of intervention.

An improved understanding of the types of suicide, who is most at risk of dying by suicide, and how we can prevent suicide is important to reverse the trend and ensure healthy futures for individuals who struggle with suicidal thinking and/or impulsive behaviors.

Just like any illness, suicide requires additional research to make sure evidence and not rumors or fear-based hunches drive prevention efforts.

What is suicidal thinking?

Most of us have wondered at some point, “I wonder what the world would be like without me in it.” That doesn’t mean that everyone is contemplating suicide. Someone with suicidal thinking, or “suicidal ideation,” has frequent or chronic thoughts about sincerely wanting to die and may even be planning how they would accomplish that goal.

If you or someone you know is experiencing thoughts of suicide, call 1-800-273-8255.

Suicidal thinking can be a symptom or component of many mental illnesses including depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, borderline personality disorder, and other personality disorders. Individuals without a psychiatric diagnosis may also experience suicidal thoughts, especially if they are experiencing economic hardship, suffering from chronic physical pain, or are grieving a recent loss.

Not all people who die by suicide have suicidal thinking; some suicide deaths are the result of impulsive or self-harming behaviors that were not intended to be fatal.

What is the difference between active suicidal thinking and passive suicidal thinking?

A lot of people, especially people who have depression, have fleeting thoughts along the theme of “the world would be better if I were not in it.” Diagnostic instruments often ask, “Do you ever think about what it would be like to die in your sleep? Or to not wake up tomorrow?” Affirmative responses to these questions would indicate passive suicidal thinking.

Passive suicidal thinking means that a person is not actively planning to end their life. They don’t have a plan. They haven’t taken any steps toward that goal.

Someone with active suicidal thinking, on the other hand, has specific thoughts about behaviors they could take to end their life. They may have even taken steps to begin to implement a plan to die.

Someone with active suicidal thinking has specific thoughts about behaviors they could take to end their life.

Passive suicidal thinking is concerning, but it does not have the acuity of active suicidal thinking. Someone with active suicidal thinking should immediately seek or be connected with emergency psychiatric care to protect their safety. Someone with passive suicide thinking should make an appointment for an assessment with a mental health professional and develop a safety plan to preplan how to maintain safety should thoughts of active planning develop.

What is the difference between suicidal behaviors and parasuicidal behaviors?

The end result of both suicidal and parasuicidal behaviors can be death. However the behaviors differ in motivation and intent. We call the behavior of trying to end one’s life “suicidal behavior,” and we call the behavior of trying to harm yourself without actually wanting to die “instrumental suicidal behaviors” or “parasuicidal behaviors.”

People who in engage in parasuicidal behaviors typically have not developed the coping strategies to deal with distress or the communication skills to express that they are in extreme pain. In some cases individuals engage in cutting or self-harming behaviors to distract themselves from pain or a sense of “nothingness.” Others may use these behaviors as a cry for help. Parasuicidal behaviors can be a symptom of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

If someone with parasuicidal thoughts engages in cutting or other self-harming behaviors and mortally injures themselves, they may die, even though their intention was to express a need for help or to try to counteract painful emotions.

The study of suicide is very complicated. With many cases, you have to go back in time to try to distinguish the difference between suicidal and parasuicidal thinking, and that can be very difficult. A thorough psychiatric assessment is important to match patients with effective mental health care for their individual diagnosis and symptoms. People who are not mental health professionals cannot distinguish between suicidal and parasuicidal statement or behaviors and need to take every suicidal report very seriously.

Predictive Factors and Risk Factors for Suicide

What are predictive factors for suicide?

Predictive factors are different than risk factors. Something is a predictive factor for suicide when, if it exists within or for an individual, it increases the chance of that specific individual dying by suicide independent of other factors.

For example, age is a risk factor for cancer. Cancer occurs more frequently in older people. But turning 65 is not a predictive factor of cancer. Age is considered among many other factors like family history and tobacco use to estimate an individual’s risk for developing cancer.

Epidemiological research has identified many risk factors for suicide completion. Predictive factors for individuals are more complicated.

The only two predictive factors that have been identified for suicide completion are:

- A biologic family history of suicide

- Having access to firearms in the home

Having a family history of suicide certainly is not a guarantee that someone will attempt or complete suicide. However, a family history of suicide or having access to a firearm in the home does increase the risk that a person will die by suicide, independent of any other risk factors.

For anyone who has risk factors for suicide, these two predictive factors are more important. They add weight to an overall equation that hints at someone’s overall risk for suicide completion. While you can’t control your family history or genetic risk, you can certainly take steps to limit your access to lethal means, especially firearms in the home. If you are concerned that someone is experiencing suicidal thoughts, an important response would be to ask about firearms in the home and take steps to remove them, at least temporarily.

Is Suicide Genetic?

There is a genetic diathesis for suicide completion. Individuals with a first degree relative who completed suicide have greater risk for suicide completion than someone matched on all other variables. Researchers are exploring the theory that something in our DNA confers greater risk, not just of developing certain mental illnesses, but specifically of suicide completion. Or, conversely, when viewed through a more hopeful lens, something in our DNA may act as a protective factor from suicide completion, regardless of other diagnoses and environmental factors.

Individuals with a first degree relative who completed suicide have greater risk for suicide completion than someone matched on all other variables.

What are risk factors for suicide?

Population-based public health studies have identified many risk factors for suicide.

Untreated Mental Illness: Untreated mental illness is a serious risk factor, particularly untreated bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. An estimated 60 percent of people who die by suicide have had a mood disorder (e.g. major depression, bipolar disorder, dysthymia).

The greatest number of people who die from suicide are diagnosed with depression, but depression is a far more common diagnosis in the population than bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. A greater percentage of individuals with bipolar disorder (4-19%) or schizophrenia (10-13%) die from suicide than the percentage of individuals with depression (2-6%) who do so.

Some psychiatric symptoms are associated with an increased risk for suicide. People who have high impulsivity as well as people who have command auditory hallucinations (voices that tell them to hurt themselves) are at higher risk for suicide ideation and suicide completion.

Feeling hopeless and powerless: People who feel powerless to shape their own lives, what we in psychiatry call people with “external loci of control,” are more at risk for having suicidal thoughts. They may feel like they have no control over what happens to them and may believe they just have to tolerate their situation and continue to suffer endlessly. Individuals with an internal locus of control on the other hand feel more empowered to take actions to improve their situation, even though the work required might be challenging or difficult. They have more hope for a better future because they can see other possible outcomes as a result of their own choices.

Experiences during childhood as well as genetics shape whether someone has an external or internal locus of control. Young people who, early in life, are given opportunities to make choices and experience the associated consequences – good or bad – are more likely to develop an internal locus of control. For adults who struggle with feelings of powerlessness, through evidence-based therapy, particularly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), individuals can work to restructure their core beliefs and shift toward developing an internal locus of control.

Other risk factors for suicide include:

- Intoxication / substance misuse – Intoxication lowers the threshold for acting impulsively. More than 1 in 3 people who die from suicide are under the influence of alcohol at the time of death.

- Social isolation or lack of perceived social support

- History of trauma, especially adverse childhood events

- Economic stress. New research points to a potential link between the minimum wage and suicide rates.

- Serious physical health conditions or chronic pain

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Stressful life events like divorce, death of a love one, or loss of employment

- Gender – More women than men attempt suicide, but nearly 4 times more men die by suicide. Men are more likely to use guns, and women are more likely to use pills. You are less likely to survive a suicide attempt with a firearm.

- Nihilistic preoccupation – when someone can’t imagine a meaningful future, or even anything meaningful in the next day

- Akathisia – uncontrolled nervous energy or inability to be still

- Bullying – Youth who report frequently bullying others and youth who report being frequently bullied are at increased risk for suicide-related behavior.

Protective Factors for Suicide

Many protective factors are the inverse of the risk factors for suicide.

Effective Treatment for mental illnesses: Access to effective mental health treatment is an import protective factor against suicide. Access to mental health services is about more than available beds in crisis units. People need access points and connections to mental health education and care throughout their lives.

Psychiatric care for mothers with postpartum depression can help families form strong attachments from birth. Research is beginning to show that mental health and mindfulness education programs for school children can have positive benefits and contribute to larger efforts to reduce bullying behaviors and anxiety. Educators familiar with early warning signs of emerging mental illnesses can help connect young people and families with treatment for early intervention. And after a diagnosis, evidence-based treatment involving medications when appropriate and psychotherapy can help people learn to manage symptoms, maintain wellness, and live a healthy life.

Acute facilities and psychiatric hospitals are important levels of care for someone in crisis. Residential treatment programs like Skyland Trail can be an important next step in helping someone develop a foundation of skills and strategies for living and thriving with a chronic mental illness. Outpatient psychiatry and therapy can help individuals continue to adjust their wellness strategies through all of life’s transitions.

A strong social support network: A strong social support network is one of the most important factors in preventing suicide. Social media and other influences are changing the way people interact with one another. As a whole, we spend less time in face-to-face interactions with people, and social interactions often are more focused on transactional goals instead of on finding common ground and building relationships. A challenging time for young people may be leaving their childhood homes to go to college or live independently. In addition to stress from new economic or academic responsibilities, they may be physically separated from their traditional support network and struggling to form a new one. Social isolation and withdrawal from social groups can be an early warning sign that someone may be struggling. Helping teens and young adults connect with peer groups and adopt healthy social media habits may improve emotional health and reduce suicidal thinking.

A strong social support network is one of the most important factors in preventing suicide.

Other protective factors for suicide are:

- Access to treatment for alcohol and substance abuse

- Economic security

- Sense of self efficacy

- Engaging in self-care activities

- Education and practice in problem-solving skills and conflict resolution

Adolescent and Teen Suicide

A 2019 CDC report cites a 56 percent increase in suicide among young people ages 10 to 24 over the last decade. Some research indicates that this increase may be related to many doctors’ reticence to prescribe medications to this age group to treat mood and anxiety disorders.

Do “black box” warning labels contribute to teen suicide?

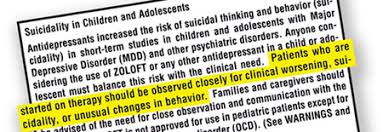

Black box warnings were added to many selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications in 2004. The labels warn of an increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in teens and young adults who take the medications.

Some research indicates that increases in youth suicide rates may be related to black box warnings on psychiatric medications.

For everyone – adults and adolescents – starting an SSRI can be very “activating” and involve risks. People who begin taking SSRIs may experience an increase in feelings of anxiety, difficulty sleeping, and restlessness. However, in the long-term, SSRIs are effective in reducing the symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders.

The view of the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is that adults can appropriately weigh the risks and benefits of SSRIs and make an informed decision to take the medications. The FDA views minors under the age of 18 differently. Minors, who might be more sensitive to the initial side effects of SSRIs, are not able to provide informed consent. The FDA also conducted clinical trials on SSRIs that pointed to a potential increased risk of suicide for young people, though the methodology and import of the outcomes are disputed. Therefore the FDA requires a black box warning on SSRI medications about the increased risk of suicide for adolescents, and physicians are therefore reluctant to prescribe them, especially in outpatient settings where the physician is unable to monitor the adolescent’s behavior and reactions during the first several weeks of pharmacological treatment, when activation is most likely to develop if it does at all.

Can adolescent residential treatment help prevent teen suicide?

Residential treatment programs, like the Skyland Trail adolescent treatment program, provide patients a safe environment to begin psychiatric medications when indicated and psychiatrists the ability to monitor the patient and make adjustments as needed.

As part of an adolescent residential treatment program, teens can adopt a positive attitude toward medication adherence early and develop skills to help them manage symptoms and reduce impulsive behaviors. Residential treatment may also reduce social isolation by introducing teens to peers who are experiencing similar issues in addition to helping them improve relationships with their families through family therapy.

Suicide and LGBTQ Teens

Studies indicate that LGBTQ youth, especially transgender youth, are more likely to attempt suicide than their peers. However the association is less about being or identifying as an LGBTQ person and more about experiencing trauma, loss, rejection, bullying, or isolation at increased rates as compared to their peers. LGBTQ teens who are part of accepting families and attend affirming schools are probably at the same risk as the general population.

Mental health treatment programs for LGBTQ youth with suicide ideation should provide a safe space for LGBTQ youth. Policies and treatment approaches should affirm a teen’s sexual orientation and gender identity, and mental health professionals should receive education and training on how best to support LGBTQ youth struggling with depression, bipolar disorder, OCD, anxiety, or other mental health disorders. (Learn more about how the Skyland Trail adolescent residential treatment program supports LGBTQ teens >>)

Evidence-based Treatment for Suicide Ideation

Treatment of mental illnesses, particularly for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, is very important to protect individuals with suicidal thinking as well as to reduce suicide rates for the population as a whole.

Psychiatric medications: Evidence-based treatment with medications has been shown to reduce mood symptoms and psychosis, as well as suicide ideation. A combination of medications and psychotherapy help many people manage symptoms and lead meaningful lives.

Cognitive behavioral therapy: Through cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), people with mood and anxiety disorders can learn to confront suicidal thoughts directly. They learn skills to recognize negative thought patterns and reframe them at the top of the funnel before they spiral downward into thoughts of suicide. CBT helps people view suicide ideation as “thoughts not facts” and use thought exercises and healthy behaviors to reduce the strength or importance of the thoughts.

DBT skills and mindfulness: Learning and practicing mindfulness and distress tolerance skills can be particularly helpful for people with high impulsivity. Mindfulness and distress tolerance are two components of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which often is appropriate for people with a history of self-harming behaviors or frequent suicide attempts. Distress tolerance gives people strategies to move through an episode of suicidal thinking without acting impulsively or self-harming. DBT is especially helpful for people with borderline personality disorder (BPD) with a history of suicidal behaviors.

Adjunctive therapies: Adjunctive therapies, offered as part of a residential treatment program or as wrap-around services in the community, can help people identify and join affinity groups and build a social network. Art, music, horticultural, and recreational therapies, along with team sports and social clubs, can help people who tend to isolate or who are uncomfortable in social situations learn social skills and experience the benefits of being part of a community. They can also help add meaning to life, provide structure for time spent alone, and encourage healthy habits like exercise and active living.

Residential treatment provides a safe and healing community during a critical time when someone is starting or adjusting medications or beginning to learn distress tolerance skills.

Residential mental health treatment: Residential treatment for adults and adolescents brings many of these therapeutic approaches together. Residential treatment can be particularly important for people recovering from an acute episode of depression, mania, anxiety, or psychosis. Residential treatment provides a safe and healing community during a critical time when someone is working toward wellness but still needs extra support, especially if they are starting or adjusting medications or just beginning to learn skills to manage pain or discomfort. Residential treatment provides 24/7 monitoring and support and a structured daily schedule. At no time of day or night are you without support, and coaching is always available. (Learn about Skyland Trail residential treatment programs for adults and adolescents >>)

What to do if you or loved one is at risk for suicide

Suicidal thinking and behaviors require support from mental health professionals. If a friend or family member tells you they are thinking about suicide or they want to die, you should automatically believe what the person tells you. Your next step should be helping the person call a crisis line, call 911, or go to an emergency room.

If you or someone you know is experiencing thoughts of suicide, call 1-800-273-8255.

Other important steps are to reduce access to lethal means (e.g. firearms, pills, knives, etc.), and don’t leave the person alone. Don’t try to manage the situation yourself; you need help from a mental health professional.

Other signs that someone may be contemplating suicide include:

- finding or receiving a note

- finding or receiving texts saying goodbye

- someone giving away possessions

- finding a stockpile of medications or some other lethal means

Take these preventive actions even if you believe the person has instrumental suicidal thinking or is engaging in parasuicidal behaviors. You want to protect that person’s life, and you also want to create a ramification or consequence if someone is using suicidal threats to mitigate hard situations.

Preventing Suicide & Reducing Suicide Rates

From a public health point of view, if we want to reduce suicides, we need to look at a variety of policies and systems through the lens of suicide prevention. We need to acknowledge the role of economics and access to mental health care in suicide rates. We need to talk about how we prevent people with suicidal thoughts from gaining access to firearms and other lethal means.

Educating families and schools about the early warning signs of mental illness can help prevent suicide.

We need to educate families and schools about the early warning signs of mental illness and build evidence-based systems for young people to receive effective treatment. We need to talk about how we can prevent trauma and support trauma survivors. We need to talk about all the barriers that prevent people from receiving quality healthcare.

We all can play a role in preventing suicides by eliminating the stigma surrounding mental illness, advocating for improved access to care, practicing self-care and asking for help when needed, and supporting one another.

Additional Resources:

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention: afsp.org

Trevor Project: www.thetrevorproject.org

The JED Foundation: www.jedfoundation.org

National Alliance on Mental Illness: www.nami.org