10 Common Types of Cognitive Distortions

Treatment for mental health disorders like depression and anxiety, particularly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) treatment, helps patients examine the intersections between their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Sometimes, we get into a pattern of accepting our thoughts or beliefs as unassailable facts. But are they?

Skill-based therapies like CBT—sometimes as part of psychiatric residential treatment programs—help individuals recognize unhealthy thought patterns that have developed over time that may be influencing their moods and behaviors in harmful ways.

Once recognized, negative thought patterns can be interrupted or reframed. Healthier thought patterns may empower individuals to make decisions and take actions that support their health and happiness moving forward.

What Are Cognitive Distortions?

Cognitive distortions are negative or irrational patterns of thought. Cognitive distortions often begin to develop during childhood and are influenced by a person’s experiences in their family, school, community, and culture. Statements from trusted adults or peers, messages received through social media or TV, adverse life events or traumatic experiences, and biological factors may all play a role.

Cognitive distortions can exacerbate the symptoms of many mental illnesses like anxiety, depression, borderline personality disorder, and PTSD. Cognitive distortions can contribute to decreased motivation, low self-esteem, depressed mood, and unhealthy behaviors like substance use, disordered eating, avoidance, or self-harming behaviors.

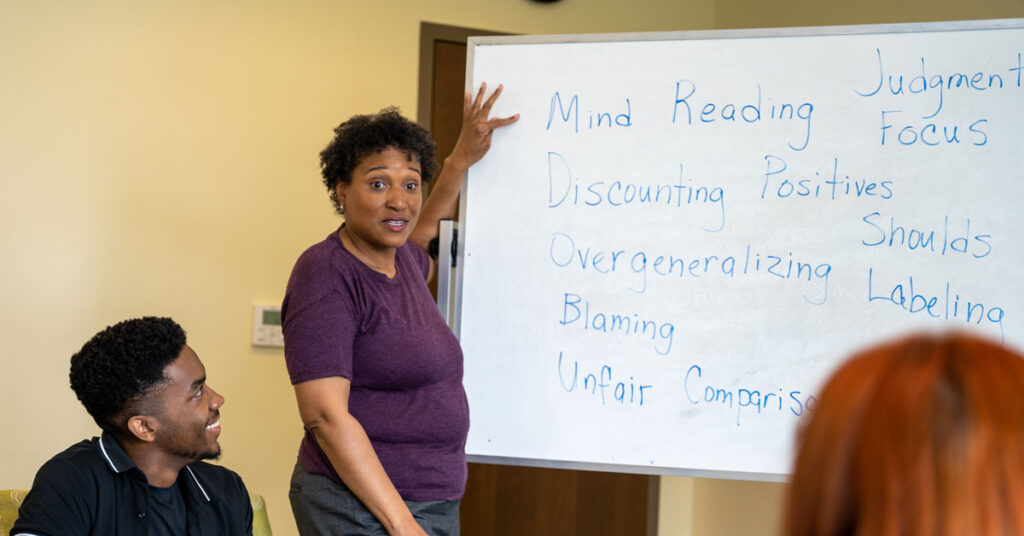

What Are Common Types Of Cognitive Distortions?

Here are examples of 10 of the most common types of cognitive distortions. You may recognize these in yourself or your loved ones. While anyone can be affected by cognitive distortions, they typically have a more significant impact on the lives of individuals with mental health disorders like depression and anxiety.

1. All-Or-Nothing Thinking

Also known as black-and-white thinking, polarized thinking, or dichotomous thinking, all-or-nothing thinking is a type of cognitive distortion that involves viewing things in absolute terms: all good or all bad, angelic or evil, perfection or total failure. There is no in-between. Individuals who exhibit all-or-nothing thinking may express thoughts like, “If I’m not perfect, I have failed.”

When confronting all-or-nothing thinking, patients are encouraged to recognize that ideas like a successful person, a perfect partner, a loyal friend, or a good parent are not all-or-nothing concepts. Success, for example, is a process of trial and error, ups and downs. And a loyal friend may still make mistakes or let us down sometimes.

We can reframe all-or-nothing thinking by making room for the “gray.” We can give ourselves—and others—more flexibility in meeting more nuanced definitions of successful, perfect, loyal, or good. Even when we fall short, working toward improvement is a valuable and rewarding journey.

2. Overgeneralization

In overgeneralization, individuals see patterns based on a single event and assume that all future events will have the same outcome. An example of this kind of cognitive distortion might be, “Nothing good ever happens to me.”

One way to combat this kind of thinking is changing our language. Instead of using phrases like “ever,” “never,” and “always,” we can describe our experiences more specifically, recognizing that each day or situation brings unique circumstances. “I didn’t do well on that test, and I think I could do better on the next one.”

3. Mental Filtering or Negative Filtering

Mental or negative filtering focuses entirely on negative examples and experiences, filtering out anything positive. Individuals who engage in negative filtering, may notice all of their failures but not see any of their successes.

Exercises to combat negative filtering help individuals highlight neutral or positive events rather than solely focusing on the negative.

4. Discounting the Positive

Similar to negative filtering, discounting the positive involves invalidating or “explaining away” good things that have happened. Instead of ignoring the positives like negative filtering, individuals see the positives but actively reject the positive aspects of a situation or person. Some examples might be, “Well, that’ doesn’t count because I had help.”

To combat this pattern, individuals are encouraged to give themselves (and others) some credit and recognize their role in bringing about a positive outcome.

5. Mind Reading and Fortune Telling

We engage in “mind reading” when we attribute thoughts, feelings, and intentions to another person, regardless of the lack of evidence. “They think I’m a loser.”

In fortune telling, an individual predicts events will unfold in a particular way, often to avoid trying something difficult. “I’m going to fail the test anyway, so why study.” “No one is going to hire me, so I have to stay in this job I don’t like.” Fortune telling can prevent individuals from taking actions to shape their own lives in positive ways.

To confront these thought patterns, individuals are asked to check the facts and ask questions to challenge their initial assumptions. If we try something different, is it possible that the outcome could be different too? Are we sure that person thinks we’re a loser, or could they possibly be avoiding conversation because they’re shy?

6. Magnification or Minimization

Magnification cognitive distortions occur when an individual blows things out of proportion. For example, someone might view a small mistake as an epic failure.

Minimization occurs when we inappropriately shrink something—like an achievement— to make it seem less important. Some people may minimize their strengths and positive qualities and believe they are not “likable.”

When bad things happen, individuals view them as proof of their failures. And when good things happen, they minimize their importance.

7. Emotional Reasoning

Emotional reasoning assumes that because we feel a certain way, what we think at that moment must be true. This kind of thinking gives emotions total control of a situation rather than the facts of the situation.

Examples of emotional reasoning could be:

“I feel embarrassed by what happened, so I must be an idiot.”

“I feel angry, so this person I’m talking to must not care about or respect me.”

“I feel guilty, so I must be responsible for this situation.”

While feelings are always valid and are “true” while we are experiencing them, feelings are not facts. Confronting emotional reasoning helps us analyze situations based on more information than just how we feel in the moment.

8. Should, Must, and Ought Statements

Framing thoughts with words like “should,” “must,” or “ought,” can make individuals feel guilty, or like they have already failed. These kinds of statements may apply an unrealistic set of rules or standards to how we measure ourselves and our lives. Society and culture, particularly social media, is full of explicit or implied “shoulds.”

Examples could be:

“I should be so much further in life at my age. I’m behind and I’m never going to get on track.”

“I should be able to wear a size 4.”

“I should be doing more to help people.”

To combat the shoulds, musts, and oughts, patients are encouraged to lean into self-compassion. While goal setting can be very useful, replace the unrealistic goals with more realistic ones and accept yourself as who you are, rather than who you think you should be. Give yourself some grace and flexibility.

9. Labeling

Labeling involves defining yourself or another person entirely on one interaction or one behavior. Rather than seeing a behavior as something the individual did which does not necessarily define them. Often times we can view someone’s behavior as who they are.

Examples could be:

“I missed an appointment. I’m completely useless.”

“He was late to our dinner. He is completely unreliable.”

Fact-checking and looking for evidence to the contrary are important ways to combat labeling. Have you remembered other appointments? Has he followed through on other commitments?

10. Personalization and Blame

With personalization and blame, individuals blame themselves, or someone else, for a situation that, in reality, involves many other factors. Good examples of personalization and blame are:

“My child doesn’t have any friends since we moved to a new city. I have failed as a parent.”

“My friend canceled our lunch at the last minute with no explanation. I must have made her mad.”

Personalization can lead to unnecessary self-blaming and guilt when there are many other contributing factors.

Strategies for comforting personalization are to 1) check your control and 2) check your responsibility. What factors in this situation do you truly control? Are you solely responsible for someone else’s feelings or reactions? Who or what else could have played a part in this?

How To Cope With Cognitive Distortions

The first step in reframing cognitive distortions is to be more aware of your thoughts and emotions and how they influence one another. Tools like an automatic thought record help patients document their thoughts, see intersections with their emotions, and recognize patterns over time.

Tools like the Feelings Wheel or a mood journal can help patients separate their emotions from their thoughts and name them. Considering a wider range of emotions can help you explore different triggers and coping strategies. Are you angry? Or are you annoyed?

Analyzing thoughts and feelings together helps us interrupt unhealthy patterns. What thoughts contributed to that feeling of annoyance? In the situation where you felt annoyed, what aspects could you control? What judgments or labels did you place on yourself or others? What information did you not have or not consider? What could you do differently next time?

Note that our bodies play a role tool. Physical sensations like hunger, temperature, or tiredness can impact thoughts and feelings. Likewise, using physical sensations like breathing exercises or changing our temperature can give us another tool to influence our thoughts and emotions.

Another way to address cognitive distortions is to cultivate a growth mindset rather than one based on success or failure. Focus on small steps in a new direction and celebrate small victories. Cognitive distortions develop over time, and working to replace them takes time and practice too.

Confronting most cognitive distortions requires viewing ourselves and others through a different lens. For people with depression and anxiety, useful tools toward that aim can be positive self-talk, self-affirmation statements, and engaging in activities that build self-esteem and self-worth like exercise, healthy eating, and supportive relationships.

Changing entrenched negative thought patterns like cognitive distortions often requires help from a mental health professional. Outpatient assessment and therapy is a good place to start. For patients who are struggling with more severe, therapy-interfering, or life-interrupting symptoms, a day treatment or residential treatment program may offer the intensive treatment needed to make progress.

This blog post was inspired by a presentation to family and loved ones of Skyland Trail clients by Crystal Battle, MFT, a family therapist and family educator in the adult mental health treatment program at Skyland Trail. An audio recording of that presentation is available online through the Skyland Trail Soundcloud account.